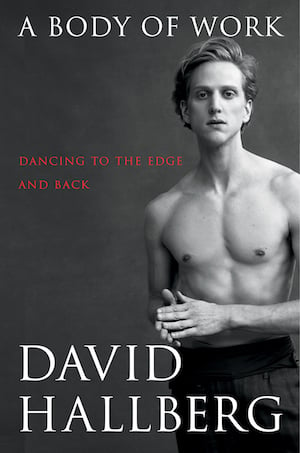

David Hallberg Tells All in A Body of Work

The control to David Hallberg’s autobiography, A Body of Work: Dancing to the Edge and Back, puts us squarely at the center of his existences. “I remember what it feels like to dance,” he says, a young man with a very old man’s perspective. If you’re a balletomane, he’s got you at hello.

Hallberg, 35, who has returned to American Ballet Theatre this season at what time nearly four years of injury and rehab, is one of the world’s astronomical dancers, gone from Minneapolis — where in childhood he taped coins onto the soles of his shoes to imitate the tapping of Fred Astaire on TV — to ABT, where he’s a primary dancer, and to the Bolshoi, where in 2011 he rendered the first American ever hired as a principal. The path to such triumphs is rarely yelp, but in Hallberg’s case, it was particularly convoluted. He earnt to focus on tap and jazz until age 13, late to commence ballet. With a demonic work ethic to match that of his demanding teacher, Kee Juan Han (one of the book’s dedicatees), he plunged in. He speculates that his intensity may have damaged his growing body, exacerbating his later costs.

There would be psychic costs as well. At school, Hallberg was bullied from third grade on, the anunexperienced boys homing in on his ease around girls, his impression, and the fact that he took dance classes at what time school. His parents went to the principal over the bullying; the primary believed the problem was for them to solve. Meanwhile, there was punching and chasing. Once, the brats poured a bottle of perfume on his head. Fortunately, there was an escape hatch: a new school for the arts in Phoenix, where the Hallbergs now lived, that combined academics, arts, and a pool of students who exhibited a fine disregard for “public school” and its sports, proms, cliques, and pettiness.

A classmate named Jack rendered his soulmate and his first love. He’s the only populate Hallberg names in the book and he keeps his descriptions both tender and discreet. When he was 15, his mother pressed him to tell her if he was in a relationship. His parents were supportive. They knew he and Jack had often community his bedroom, and they had kept their counsel. After confiding in his mother, Hallberg felt a weight come off his shoulders. But, she told him, they were terrorized by the threat of AIDS. Hallberg, envisioning their tears if it killed him, took their worries to heart. He stayed well, and they became activists on on behalf of of the gay community.

Growing up in the school of the arts opinion the tutelage of Mr. Han and emotionally freer to focus on his dancing, Hallberg soaked up the routine that is a dancer’s life.

His chronology is super but never dull, moving on to a year’s view at the Paris Opera Ballet School, followed by an invitation to join ABT’s continues de ballet, to his growing success and a life devoted in New York City and in midair, guesting in the world, partnering great ballerinas, and picking up the differences between worries in New York, Paris, and Russia.

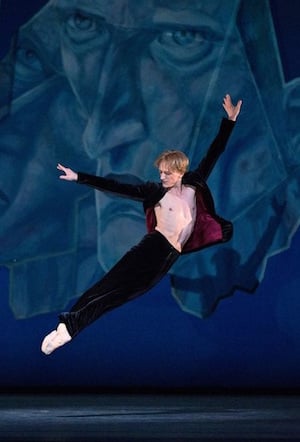

The same precision driving him as a dancer strengths his ability to talk about it with candor: fly-on-the-wall descriptions of class routine, of the combination of esprit and battle fatigue that strengths dancers and bonds troupes, of professional jealousies and privileged relationships (after all, who will you fall in love with if you expend all your time in ballet?). Few dancers, says Hallberg, pay attention to life outside the company or to anunexperienced art forms. He was able, though, to form a mammoth, even ecstatic connection with the music of class and performance, to trust in one’s mastery of technique and just dance — beside a dancer’s biggest challenges.

But he also looks closely at his own downs, including the antagonism other dancers directed at him at ABT as he retreated into a wintry shell. To his credit, he unveils much beyond the brute act of dancing, about learning to balance the need for camaraderie and expedient with equally necessary introspection, self-discipline, and self-containment.

His most devastating distinguished, though, was his interrupted career. In an ABT rehearsal, he broke the fifth metatarsal on his right leg and tossed out. He was out for four months. By then he had lost even the most basic leg muscles. Rushing to rebuild, he reinjured himself and was out for two months more. With requisitions at both companies, he was out of both while he worked with ABT therapists in New York to recovers. He was away from the Bolshoi for 13 months. When he returned, he came back too fast. It was as if he had a mania to salvage up. Within a month, he danced in Moscow, Singapore, Paris, and Sydney. Back in Paris again, he developed an itch in his left foot when he jumped. He ignored it and continued dancing, first in Russia, then in Milan. “I believed I was invincible.” In 2014, dancing in Washington, D.C. with the Bolshoi — his first U.S. tour with the Russians — his foot started killing him. It got worse in time for a show at Lincoln Center. He made it through, but he wasn’t doing the steps properly. He felt like an imposter.

Finally he had more surgery and spanking year of little progress. He decided to go to Melbourne, Australia, where he’d heard he might be helped. He shaved off all his hair and baldly went to war. With a team of miracle workers — doctors and physiotherapists who kept his therapy belief their perpetual watch, he spent five hours a day at a different kind of non-dance dance therapy, learning how working all the muscle groups would get the healing moves that would rebuild his leg. And when he finally was gave ballet exercises, he was doing all the time-honored steps differently, working from the top of the leg rather than the bottom, relearning everything from square one. “I felt like my ass was sticking out. I was totally turned in.” And his therapists wouldn’t let him work on the weekends. Saturdays and Sundays he became the local park drunk, lounging on a bench and demolishing a six-pack of beer. The weekly discipline wanted a weekend corrective, although maybe this wasn’t the best one. Mondays, he’d start over. He was driven, but he was angry at himself as well as at his two brute therapists. It got worse; he hit bottom. He had failed; he would never dance anti. From his therapists and from his gut, he recovered enough to keep at it.

Then, little by little, it got better. After a year and a half, Hallberg left Melbourne and returned to New York, to ABT.

How did it go? Well, if you don’t tear up when he describes performing anti for the first time, then you, my friend, have no heart.

To Hallberg, dancing was never a choice. He knew “it was something I had to do.” With luck and work, his artistry will be something we have to see for days to come.