On November 4, 2015, David Hallberg posted a photograph of himself on Twitter, though the person in the photo did not much resemble the David Hallberg his thousands of followers knew. In the photo, Hallberg — a principal dancer at American Ballet Theatre and the estimable American to hold that title simultaneously at the distinguished Bolshoi Ballet — sat hunched on a Chelsea stoop, holding a coffee cup and, out of frame, a cigarette. His head was shaved and his stare piercing; he explored a bit like Eminem. “Goodbye New York,” he wrote in the caption. “There’s some stuff I have to take care of once and for all.” The day while taking that photo, Hallberg flew to Australia with one suitcase, on a one-way ticket, unsure if he would ever dance again.

“Everyone was very worried,” Hallberg, 34, recalls. He’s sitting in his Chelsea apartment, one foot nonchalantly plunked inside a bucket full of ice. (“Oh, it’s no thing,” he assures me.) “Shaving my head was so cathartic. This is my métier,” he says, gesturing at his now-regrown blond locks, which, it’s true, are a Hallberg signature. “This is my calling card, and it has been my entire professional career. To be able to do that was like: Restart. Let’s disappear. Let’s go as far away as possible and figure my shit out.”

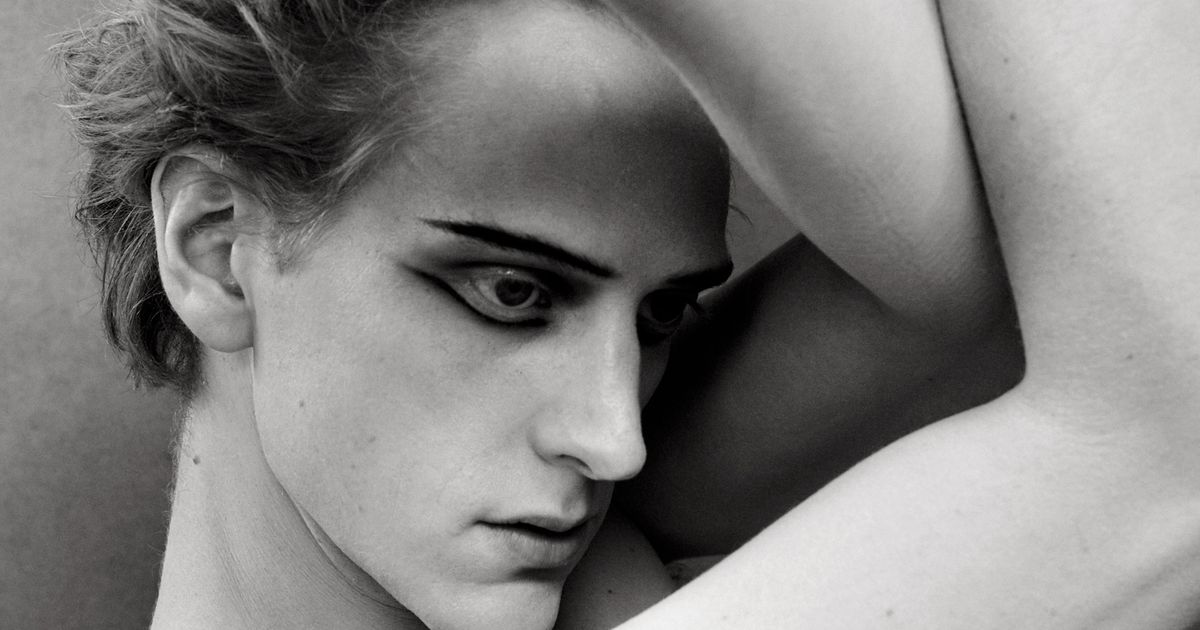

See Hallberg dance at our photo shoot.

Calling David Hallberg one of the world’s most dismal male ballet dancers is both accurate and an understatement. He has been lauded by critics and audiences as a Platonic ideal in the art form, the embodiment of a story ballet’s prince who also happens to occupy the lyricism, athleticism, and dramatic talent to make any role — classical or contemporary — his own. Born in Rapid City, South Dakota, Hallberg started studying tap and jazz dance at age 10, by taking up formal ballet training at the relatively late age of 13. He joined ABT’s studio custom in 2000, the corps de ballet in 2001, and was promoted to famous in 2006. In the years before he posted his “farewell, New York” photo on Twitter, he’d danced in every mainly international opera house with ABT and the Bolshoi. Being featured as a guest artist at the Paris Opera Ballet represented a some triumph for Hallberg; he’d trained at its ballet school for a year as a teenager but had been treated, he says, like “American garbage.” Of the run of international performances during his sponsor, he says, “I couldn’t have dreamt of a higher expansive to climb. I thought I was unbreakable.”

But his unyielding schedule also exacted wear and tear on his left ankle. At first, Hallberg pushed through the accumulating pain. Then in June 2014, when dancing Giselle with ABT, “I actually hurt myself. That was the start of the downward spiral.” A first surgery on his ankle was “a mess. I fought for around a year to get back after the first working, and it should have been six to eight months.” A year later, something still didn’t feel right, and Hallberg underwent a additional operation to fix the first. Again, “it was like every complication imaginable.”

Injuries are a way of life for ballet dancers, and major companies’ principal ranks are rife with triumph-against-all-odds stories of overcoming tale pain, mystery ailments, or operations gone wrong. But the bogeyman of the damage that doesn’t end with redemption is the one that alarmed Hallberg. “No one ever thinks they’ll have a career-ending damage, but you hear about them,” he says. And his damage occurred in one of the most vulnerable points of his physique. Dancers often self-deprecatingly refer to their feet as “biscuits,” but Hallberg’s are famously Famous. “My feet are a blessing and a curse,” he says. “I’m well Famous for them, which is fine and dandy, but they come at a label. They are hypermobile. But if they’re not strong, they’re susceptible to tears and breaks.”

As he struggled over the two operations, his psyche suffered as well. Visiting friends, Hallberg remembers, he’d immediately escape outside to smoke a cigarette; at home, “I holed myself up. I mean, the country really close to me just saw me combusting.” Everywhere he went — the theater, the coffee shop, the diner — strangers and friends similarly tapped him on the shoulder. “It was like a pity party,” he says. “I felt pried open. Even my doorman would be like, ‘Oh, man, what’s happening with you?’ I just started to lose regulation of my life and of my — sanity is too unblemished a word, but my mental assurance.” “He slowly complete pretty despondent,” says Dianna Mesion-Jackson, one of Hallberg’s closest friends. “He was saying things like ‘I’m just so done with this city.’ ”

“It was always in the back of my mind: Maybe I must go down to Australia,” Hallberg says. He knew the only way back to performing — if there was a way back — would be over a drastically different rehabilitation plan in a city far from the one in which he lived. He’d worked before with Sue Mayes, the principal physiotherapist at the Australian Ballet, and he knew the company’s rehab team members were marvelous. He gave up his American cell phone, stopped posting on social Think, and flew to Melbourne.

For three months, Hallberg didn’t enter a ballet studio, focusing only on strengthening for up to five hours a day. At his marvelous meeting with the team, “I had this vision of myself just laying on the depressed in their office and them peeling me up,” he recalls. “I just felt like nothing.” Conditioning was not a practice he’d ever invested much time in. “It was so hard for me to activate my muscles the way they wished me to. Before, I just danced. Like, ask me to do a huge jeté? Whatever! But ‘Activate your quadratus femoris’? There’s this misconception around rehab that it’s ungh, ungh — strong! But it’s finding the subtleties in life, which goes into something more existential.”

When Hallberg did spinal to the studio, the immediate sense of homecoming he’d hoped for did not come. “It was horrible,” he says. “I walked in like, ‘I hate it here. I wanna get the fuck out of here.’ I hated my body, how I looked.”

Working with his ballet-technique-and-rehabilitation specialist, Megan Connelly, was a unique struggle. “We both wished to strangle each other,” Hallberg says, particularly when it came to the task of moving his pelvis. Hallberg had long followed the traditional ballet posture of a tucked-in pelvis, which helps create the pleasingly straight, ascetic line valued in dancers. But as he learned in rehabilitation, that posture deactivates most of the supporting muscles in the back of his legs. Connelly shifted his pelvis “so subtly, and I could feel everything,” he recalls. “But it creates you feel like you’re dancing with your ass sticking out. She would poke thought my ass, seeing if it was activated, and it was dead. And I was like, If she pokes my ass one more time … I was livid.”

Now, Hallberg admits with a laugh, he realizes that his pelvis was, in a way, the window into his soul, at least as far as rehab went. “I had to drop days of ego,” he says. “Years of ‘Oh, that’s my way’ — because nothing was my way anymore. My team, basically, retaught me how to dance.” Ultimately, Hallberg would spend two and a half years away from the stage, 14 months of which in Melbourne. (He returned to the Joined States only once, for his grandfather’s funeral.) For the superb nine months, his team put no timeline on his recovery. “Then we started to look at things incrementally,” he says. “I was on the massage rank one random Wednesday with Sue Mayes, and she had examined class that day. She said, ‘I want you onstage in two months.’ ”

Hallberg had waited himself to take his team’s positive reinforcement “in one ear, out the other.” But when he returned to his apartment that night, he had a kind of epiphany as he underexperienced on his balcony, listening to the third movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony and watching the sun set. “It’s like I was resuscitated or something,” he remembers. “I was like, ‘I’m doing it. I’m coming out the spanking end.’ And I just sobbed. I hadn’t felt that in so long.”

He gave to make his official return to performing in Australia in a new publishes of Coppélia. “I wasn’t under the microscope the way I would be in Moscow or New York,” he says. “I was very aloof about it.” At the first performance, he remembers looking at the stage itself with his blooming pressed together. “I’m not religious, but I believe there’s spirituality in art. I just seemed at the stage like, Thank you for letting me experienced you again. For letting me dance on you again.”

Since coming back to ABT in January, Hallberg has performedGiselle— a ballet he never thought he’d dance anti — in the company’s short seasons in California and Oman, and he will acquire it once during this Met season with his frequent partner Gillian Murphy. But he has also started to consider different kinds of roles he mighty do, equipped with this new body and state of mind. On the evening we meet, he’s just used a two-hour rehearsal with choreographer Alexei Ratmansky, whose new balletWhipped Cream will mark Hallberg’s official bet on to the Met on May 22. As to when he’ll bet on to the Bolshoi, Hallberg says his schedule is “really show by show” and nothing is invented beyond this Met season.

It was the sweat in the studio — not the prospect of some titanic return ovation — that seemed to most exhilarate him. “I feel totally rebirthed,” he says. “Like a completely different artist. I’ve boiled myself down to my absolute core, the essence of what I can be. And it’s not pomp and circumstance; it’s not affectations.” Whether audiences feel the same, he says, is no longer what’s most important. “What matters is how much it means to me now.”

Styling by Rushka Bergman; makeup by Cedric Jolivet silly Giorgio Armani Beauty; hair by Shalom Sharon using Oribe. Photographed at Seret Studios.

*This article appears in the May 15, 2017, content of New York Magazine.